Race, Ancestry, Heritage, Nation, Belonging Race, Ancestry, Heritage, Nation, Belonging ON RACISM AND HERITAGE IN DAUGHTER OF ODYSSEUS. PART ONE 1. Introduction: I don’t like this word. Racism. Why you say? It would have to be one of the most misused and abused words. Others will argue that there are no races therefore there can’t be racism. Some say there is a sinister agenda behind the use of the word, and many dread being labelled as ‘racist.’ Some say that only whites are racist and can’t themselves be victims of racism. This simply is not true; we are ALL potential victims of ethnic hatred and discrimination I won’t delve into these arguments. What I do know is that there are different ethnicities, races, tribal groups amongst humanity. Differences exist. Humans have for centuries lived in geographical locations amongst people of their own race/ethnicity/tribe. That this race shares similar physical characteristics as well as customs and cultural traits. It is common for people to gravitate towards their own even in multi-ethnic countries such as the U.S.A, Canada and Australia. This includes friendship and marriage/relations. So, when people who were once geographically isolated from another group of people, now live in the same location as that group, there is going to be an element of hostility. It is inevitable I believe, as humans are tribalistic deep down. You don’t have to agree with me, but when things get tough, utopian ideas such as ‘We are all the same’ etc won’t hold. This is unfortunate but the truth in our current state of affairs. So, there is going to be what is now known as ‘racism’: hostility and hatred towards that which is different because of their ‘race’ and/or ethnic heritage. European colonisation, tragically, was rooted in racial superiority which means if there is a ‘superior’, there is going to be an ‘inferior.’ Colonial literature gives a good glimpse of the hatred displayed by, for example, the British towards the Indians and other ‘natives.’ It is vile to say the least. Australia itself was built on the conquering of the white British of a land once occupied by the Aboriginal people. You could not get two more opposing tribes of people, so utterly unlike in radical ways. Unlike in appearance, clearly, but in spirituality and customs and attitude towards the land. The conquest of Australia was brutal. There was genocide, there was a strong belief rooted in Darwinian theory that the Aboriginals would die out and the ‘half-castes’ would eventually be bred so that their Aboriginal ‘blood’ would be ‘weeded out.’ Yes, this description is evil, but what the British did was evil. Yet the British insist they are the bastions of freedom and democracy. The hypocrisy is mind-boggling. (Note, I am not condemning the British as a whole: I don’t believe in generalisations and know there is good and evil amongst all peoples). Into this land of genocide and racial supremacy came the Greeks, this southern European people whose dark hair and dark features distinguish them from the northern Europeans. Yes, there are fair Greeks but they can easily blend in. The southern Europeans were treated cruelly. Of course, there were the racial slurs: wog, greaseball, spaghetti eaters, dagoes etc etc. Words spoken with pure hate. There was the bullying, the humiliation of those with ‘ethnic’ features, the fear that the Greeks and other non-Anglos would take over the country. Some Greek women, just to survive psychologically, completely assimilated, married Anglo-men and abandoned their heritage. This was my reality as a Greek-Australian. Yes, I experienced kindness and compassion from people of British and other descent; I am not generalising by any means. But when you experience ostracism, dehumanization and nastiness because of how you are born (something beyond your control), a part of you dies. I have had some shockingly nasty things said to me, and often by northern Europeans who insist on their ‘purity.’ What shocked me was the sheer malevolence of their words and tone. I look Greek. I look ‘ethnic.’ I don’t look northern European. I have relatives that do, and they can fly under the radar, but not me. When I say ethnic, I do mean large dark eyes, olive skin and, yes, an ‘Aquiline’ nose. I have a Romanesque nose in a land of small, snub noses. And it has been pointed out to me – many times. And somehow it makes me less than human. Yes, humans are a weird bunch. As Kermit the Frog once said: ‘It’s not easy being green.’ Well, it’s not easy being ‘ethnic.’ As I already said, a part of me has died with what I have experienced. My innocence, my sense of worth and humanity. It is still with me; it will always be with me. I have experienced vitriolic racism even as a teacher, and this just in the last few years. By students, by those students I sought to elevate and inspire and help in so many ways. The hatred that poured forth was really like a slap in the face. Some people have the ability to shrug it off. They are tough. I admire them. I am sensitive and words do hurt. Whoever invented the saying: Sticks and Stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me, was a liar. Words hurt, brutally so. As the Bible says: And the tongue is a fire, a world of iniquity. For every kind of beast and bird, of reptile and creature of the sea, is tamed and has been tamed by mankind. But no man can tame the tongue. It is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison. With it we bless our God and Father, and with it we curse men, Out of the same mouth proceed blessing and cursing. (Epistle of James) Ethnic. The Other. An exotic plant amidst sunflowers. This has been my experience. This is the experience of Christine, the heroine of Daughter of Odysseus. She is a heroine, no doubt. She suffers but strives and perseveres; always perseveres. 2. Greek? Who cares? When we first meet Christine, as a teenage girl on the threshold of adulthood, we meet a character who had not given much thought to her Greek heritage. Ironically, of course, as this is what created her sense of ‘otherness’ and suffering. You see, Christine sees herself as normal; just another teenage girl obsessed with pop stars and socialising and checking out hot young men. The fact that others pointed out her differences hurt her no doubt, but she still tries to live a normal life. But her Greekness is always there, like the air she breathes. Subconsciously. So, as she prepares for an evening out on that Christmas Eve, she reflects on the night ahead at a gathering known as ‘Greek Night’: It was not uncommon for Greek girls to lose their virginity on nights like these. Greek Nights, when the young Greek-Australians of Adelaide gathered at a designated bar to share in their Greekness, the latest hits from Greece played alongside traditional songs and created a bond. People joined hands and danced traditional dances in circles, as brothers and sisters sharing the same ancestral heritage. They were united . . . for a few minutes. Christine relished these moments. Something within her stirred—she couldn’t quite put her finger on what. She had never given much thought to her Greek heritage. It was just something that was there, like air. Greek School was a boring chore to make her parents happy; Greek Dances were a time to dress up and admire young men from afar. But hands joining to dance the Kalamatianós was akin to a secret magical rite. (Daughter of Odysseus: Ithaka Calling) Born in Australia, thousands of kilometres away from her ancestral homeland, yet something as simple as dancing with others of the same ethnic background transforms Christine into another person. Something stirs within her, the blood essence, her ancestors moving within her, call it what you will. It is something intrinsic to all of us. It is magical and worthy of preservation. 3. Is this my homeland? It is only as Christine plunges into severe depression that she begins to delve deep into philosophical concepts such as: who am I, where am I, what is the meaning of life? She was born in Adelaide, Australia. She lived in the suburbs, on land once belonging to another tribe. Now taken over by another tribe. Both tribes extrinsic to her. And it is as she wanders these streets that she plunges into almost a state of shock, an awareness that leaves her questioning. That something is not right. All of this, her being in this place, is smothering her. She looks around her as she is wandering and is confronted with something macabre, something monstrous: When did it come back? When did she first see the black clouds hovering above her, dispelling the light she’d revelled in that morning? They’d swooped over her so quickly, so unexpectedly that she’d fled the mall. Or were they unexpected? Could depression be banished so easily, this demon of death, this black hound? The streets led her here and there and nowhere. They took her past houses with high fences and closed doors. Past snarling dogs and old ladies with purple hair who smiled but looked through her. Past leering men with beer guts and flannel shirts: men wallowing in their sleaze, in their monotony. Monotony . . . monotony. . . . A car screeched by, and the gorgons inside glared at her, daring to turn her to stone. They hollered obscenities. She continued to wander, like a nomad, like the first inhabitants of this country. (Daughter of Odysseus: Ithaka Calling) Extreme perhaps. Is she really being smothered and harmed in any way? Surely her depression means she is looking at the world through distorted lenses that are a reflection of her blackened state of mind. You see, Christine is not living life to her full potential as she should be, as she deserves. As we all deserve. So yes, she is being smothered, poisoned; she is drowning in a sea of nihilism and nothingness: Adelaide, Australia. A land that had once been the home of the Aboriginal Tribes of the Great Adelaide Region, whose belief system taught that everything in the physical world was touched by the footprint of ancestral beings that had walked the Earth, shaping the landscape and establishing the rituals, rules and laws that guided them. The spirits had disappeared; the storytelling and songs were silenced; and a foreign body now occupied the sacred land. But the silence, the emptiness was deathly to her. Christine felt like a stranger, an alienated and isolated creature, segregated from this country, its people and its history. Neither indigenous Aboriginal nor descendant of the British colonists, there was nothing she could relate to, nothing that inspired her and infused her with purpose. The thought of this—the first time she had had this thought—overwhelmed her. She panicked. Her breathing became rough, desperate. She imagined herself in fifty years’ time, roaming the same streets with the same feelings of mind-numbing nothingness. Streets and suburbs that once upon a time felt like home were now hideous warts covering this country. All she could see was a dead heart and a people she could not understand. (Daughter of Odysseus: Ithaka Calling) She is stumbling, dazed as it were. As if true to the words of a Greek poet: that this is not my country but I ask, what is? What do I wish? she wondered desperately. What do I want? I, who am exiled on this island? The answer came instantaneously, as if it had been waiting to emerge all this time. She wanted a world transfigured, magical, and divine. She longed to see the Earth arise out of her chaos—beauty out of ugliness. She desired to walk the land of her ancestral beings, to find her roots and blossom, to bear rich fruits and thrive in her land. (Daughter of Odysseus: Ithaka Calling) And so, the search begins. A search that, at its heart, is to find a sense of belonging and pure joy and love. A search away from ethnic hatred, of racism and dehumanization. A search that, if it must, lead one to traverse seas and lands to find that concept that is intrinsic to humans. The search for home. For Part Two, click on the below link: http://www.vasilikim.com/blog/on-racism-and-heritage-in-daughter-of-odysseus-2

0 Comments

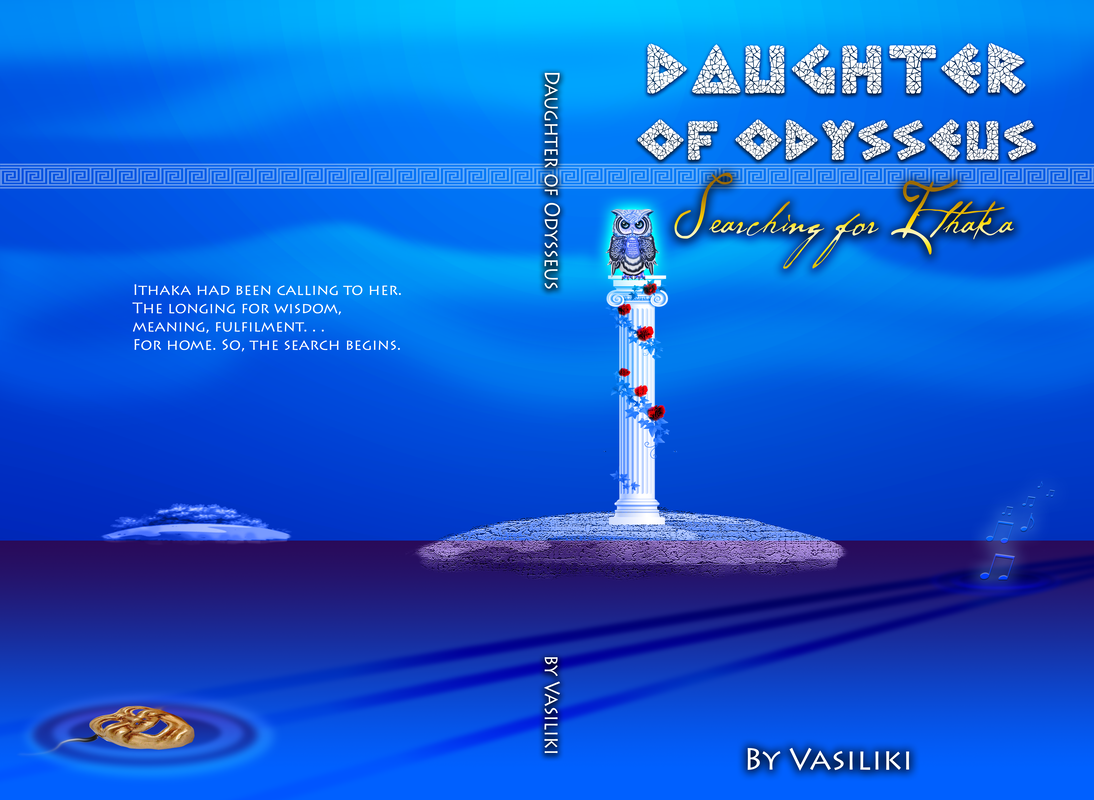

IDENTITY (My character Christine from - Daughter of Odysseus - reflects on her identity) ‘There was a time when everything was still,’ Christine would say to her captivated audience with such eloquence and persuasiveness. She had a story to tell and how she longed to tell that story to anyone who cared to listen. . . ‘All the spirits of the earth were asleep—or almost all. The great Father of All Spirits was the only one awake. Gently, he awoke the Sun Mother. As she opened her eyes, a warm ray of light spread out towards the sleeping earth. This story has resonated with me since I first heard it. Like me, the Aboriginals of Australia sought to understand their world, their land, their relationship with the physical and the sacred through telling stories of the creator and the seed power that permeated the earth. Nothing in the physical world was untouched by the footprints of the ancestral spiritual beings who walked the earth, shaping the landscape and establishing the rituals, rules and laws which guided them for centuries. And then, as the narrative goes, an almost pristine existence was destroyed by the British, who came to Australia like the Ancient Israelite's entering the land of Canaan, seeking a land flowing with milk and honey (well, a prison for its burgeoning prison population thanks to draconian laws) and treating its native population with friendliness at first, then cruelty. Not understanding the Aboriginal spiritual relation with the land, the British saw a land unconquered and available for the taking and therefore declared the land ‘Terra Nullius’—no one’s land. They tamed this hostile, arid land and transformed it into Little Britain, building modern European cities away from the uncivilized and threatening desert. This was an admirable achievement and showed a spirit of brilliant creativity, hard work and—dare I say it—technological supremacy. The Queen ruled as Head of State, and the White Australia Policy ensured that this small country of western origin remained just that. The original people of the land were soon forgotten, exiled to the outskirts of growing cities, converted, terrorised, hunted down, so that this country became their prison too. Darwin’s theory of evolution, in fact, demanded this. Thus, time passes: the establishment of a nation, the glory of war, the post-World War II boom and the influx of migrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. This is where my story begins, where my creator planted me for reasons I am yet to fathom. Yet the Australia I grew up in was one undergoing a radical metamorphosis—a society changing from a purely British colony to a multicultural society. An ambiguous term, multi-cultural; an ambiguous and unrealistic concept, it meant the ruling Anglo-Celtic elite could dine in exotic restaurants, eating exotic foods and flaunting their ‘exotic’ lovers and thereby somehow make amends for the sins of colonialism. Thus, they came, my parents, amidst the swinging 60s and the chance of a new life. Yet they preserved centuries-old traditions and values that distinguished them from the Anglo-Saxons, and they waited in patience to return to the motherland, prosperous beyond words. Discriminated against, accused of ‘taking over the country’ (I know, ludicrous!); some assimilating and eventually disappearing altogether. And slowly, these immigrants forgot their homeland, sought houses in suburbs with pretty picket fences. Anglo-Saxonized their names and abandoned the mother tongue. They sent their children to private schools to get a British Education of the highest sort; they established their roots in this land of the Great Spiritual Beings and British Supremacy. They did this whilst the Greeks in the motherland sang Songs of Freedom against a Military Dictatorship that took power in Greece and lived in fear of arrest and torture. Black Australia, British Australia, and Multicultural Australia. Now what? A modern yet ancient land that seems to know neither its place nor its position in the world. Its people feel alienation within a land that perhaps, just perhaps, is foreign. A country that I seek to understand, that has the grace and sophistication of a gawky teenager eagerly waiting for the wisdom and cultivation that adulthood brings. As I confront this mosaic before me, I ask: where do I fit in this multi-faceted, vast continent? I, the daughter of the Hellenes, who resist assimilation, who will not allow the wisdom of my ancestors to be forgotten or ignored? Mine is the life of a Greek Australian woman. I am the offspring of a fiercely patriotic Greek father who lives enclosed in an ethnic bubble and has no dealings with the Anglo-Australian population and refuses to learn their ‘barbaric’ tongue. The offspring of a mother who once upon a time longed to return home, grow old and be buried in the motherland, but who has resigned herself to the reality that Australia is to be her burial land; that this Greek woman will spend eternity among the alien spirits that once roamed this diverse terrain but now remain hidden in the land, weeping at the destruction and desolation of its children and the sacrilege against sacred ground. ‘Where are you from?’ ‘Are you Australian?’ Ah, how I detest these questions; how they eat away at me. What am I? Neither Aboriginal nor a descendant of the British—now the true native people of Australia. Neither here nor there, neither Greek nor Australian. Juxtaposed between two worlds, I live an ambiguous existence. Born in a country that sees me as the ‘other’, I nevertheless cling to a Greek heritage and culture that appears strange to me; I seek to re-learn the mother tongue and find solace in the unbelievable Spirituality of the Greek Orthodox Church and the Byzantine heritage forgotten by the modern western world. I write of the Greek Community in Australia whilst studying the Great English Poets whom I love with a passion. Alas, this ambiguous state is the norm for this young country, for its inhabitants. Identity. You Greeks in the motherland do not need to worry about this. You know who you are. You know where you belong. In a land that has nurtured you and your ancestors for thousands of years. Among the majestic mountains and along the enigmatic sea that has enthralled your forefathers for centuries, that has infused the land with stories of nymphs and gods, stories of holy men and women working towards the Kingdom of God. The great Saints of the Church who continue to roam the land in all their miraculous glory, healing the sick and restoring faith to the doubters. My vision will be fulfilled; I can feel it. Of climbing the steps to the Acropolis and exploring medieval towns. Scaling primordial mountains that once were the abode of the gods; exploring sacred land where my ancestors once came to listen to oracles that foretold great and tragic events A flower uprooted from its nutritious soil—from its native soil—withers and eventually dies. Plucked up and displaced, forced to grow in an alien land that I have never truly felt at home with. Will things change for me? Only time will tell. . .  The Story Behind the Image A reflection on a book cover. I have to say, I struggled with the cover design of book two of my series, Daughter of Odysseus: Searching for Ithaka. I know book covers are important; they are the introduction to the book, the image and design that encapsulates the words within the pages. They can entice, inspire and fascinate. They can be truly illustrious or downright tacky. I hope I don’t fall into the second category. I ahhed and ummed about the final product and still do, to be honest. But I believe the book cover for Daughter of Odysseus: Searching for Ithaka, captures the story, its themes and motifs in vivid ways. It is a cover rich in symbolism, from the owl sitting on top of the Greek column, to the mask floating within the waters of the sea; floating within the trail that represents the ship travelling and searching for home, for Ithaka. Bird symbolism plays an important role in book two. Each part has a bird symbol: the cardinal, the owl, the peacock and the eagle. I chose the owl for the book cover because of its supernatural connotations, its association with the goddess Athena and its links to the concepts of Wisdom. Athena was she who guided Odysseus throughout his journeys. She encouraged him, protected him, ensured he grew in wisdom and certainly stature. She transformed him physically many times, from a lowly beggar to a man akin more to a god. The idea of Wisdom is also important. It is a theological and philosophical concept, appearing in the Old Testament through the Book of Proverbs, for example. Wisdom is symbolised as a woman calling passers-by to hear her voice, to discern truth and to walk in the paths of righteousness and justice. She is the opposite of Woman Folly and indeed is so important that the Bible says that she was with God at the beginning of Creation. Thus, Wisdom is associated with creation and her principles and laws can be found even in the lowliest of ants. Although bird symbolism plays a key role, it does so in a subtle way, enhancing the theme and motifs of each part and giving us further insight into the life of Christine, the people around her and her journeys. The bird can appear at any given moment; in a painting, on a necklace, within the embrace of a lush forest: From this scenery of pure loveliness, Christine caught a glimpse of a bird arrayed in the robes of heaven. She rubbed her eyes and looked again; sure enough, she could discern none other than a peacock standing erect; his dazzling cloak of feathers lying flat and encircling his body, his head with its shimmering blue upright and looking towards the bus, his coat of a hundred eyes that her ancestors would have seen as symbolising the ‘all-seeing God’—eyes that encapsulated the glories of the heavens above. Such nobility, such grace, such confidence! This image of the peacock infused within her vivacity of spirit, mind and body. It inspired her to believe in her own self, to embrace the dignity and self-assurance that, surely, was buried deep within her and now ready to find fruition. The column, of course, represents Greece. What could it represent otherwise? A land of crumbling ancient columns from temples dedicated to the gods and goddesses worshipped by my ancestors. Majestic structures of symmetrical perfection and aesthetic wonder. This is a book in Greece, about Greece, and ultimately the role Greece plays and has played in the history of humanity, as well as in the life of Christine. A mysterious land, multi-faceted, ancient yet intensely secular and materialistic. A world of pure spirituality and terrible moral corruption. A land of holy monks and not so holy people. A land rich in natural beauty, yet oftentimes full of people blind to this beauty. The musical notes emanating from the trail of the ship, from within the deep recesses of the waters, symbolise the Sirens. The Sirens were water nymphs who, although bewitching to sailors, had the power to lure and destroy. It was their singing that held the power and that so entranced the traveller of the sea to forget their homes, their wives and children, only to be led to their death. ‘Woe to the innocent who hears that sound!’ Odysseus is warned. Indeed, so powerful was their beauty and bewitching charm that Odysseus had to be tied to the mast in order to still be able to hear the Sirens singing. Of course, he begged to be untied upon hearing their voices, as he succumbed to feminine temptation and all its trappings. There are metaphorical sirens in Searching for Ithaka trying to lull Christine away from her journey and from that which she is searching for. These sirens manifest themselves in many ways: through the people she meets, the moral corruption permeating Greece (and enticing her), the promises of pleasure and hedonism and materialistic superficiality. The temptation to not be who she truly is, to find a false Ithaka detrimental to her well-being and her soul. A temptation that leads to her spiritual death. Parallel to these musical notes, on the back cover, is a golden mask floating menacingly in the waters. It is gold and shimmering and brilliant. The symbolism of the mask is well-known: concealment, falsehood, illusion, disguise, deceit. There are masks all around Christine: on the people she meets, within herself, and ultimately, the mask she has created about the land of her ancestors, Greece. Masks that she must tear away and find the truth; masks that reveal a rotting body and a distortion of reality: ‘Look beyond the veil Christine,’ she could almost hear it say. ‘With Wisdom by your side, learn to see what others do not; tear off the masks of those around you—of the world around you. But most importantly, tear off the mask you are now wearing and look deep into your own self.’ A Book Cover should never be just a pretty picture or an afterthought. It must capture the story within and in a sense, be its own story. I hope I have achieved this.  Man’s Best Friend: A reflection on Argos the Dog Homer’s Odyssey is a masterpiece of literature, rich with vivid characters and mythological wonder; there is adventure, suffering, joy, hospitality, love, loss and the imminence of death around every corner. From Circe the Witch who transforms men into swine, to Cyclops who gobble up men only to fall asleep content, to a wife weeping for the loss of her husband, it has something for everyone. Yet the story that touches me the most is one of a dog named Argos. He only appears briefly in this epic. He is most pitiable, wretched and near death. He is a victim of clear neglect and abuse, and one weeps when the hero, Odysseus, sees the dog for the first time after some twenty years. You see, this is Odysseus’ dog, now dumped outside the palace and sitting upon dung. He was the dog of a King, a hero, a hunter’s dog with skill and grace and strength. As we learn: While (Odysseus) spoke An old hound, lying near, pricked up his ears And lifted his muzzle. This was Argos, Trained as a puppy by Odysseus, But never taken on a hunt before His master sailed for Troy. The young men, afterward, Hunted wild goats with him, and hare, and deer, But he had grown old in his master’s absence. Treated as rubbish now, he lay at last, Upon a mass of dung before the gates – Abandoned there, and half destroyed with flies, Old Argos lay. The image is descriptive, haunting and brutal. Homer dedicates a number of lines to tell the reader of the suffering of this once majestic creature. He is abandoned, with his master gone for so long, treated as rubbish by the parasites now flocking to the palace to steal Odysseus’ wealth. Argos is in anguish, clearly, with no one to care for him. Once used for hunting expeditions, he is cast away in his old age. His master is no longer there to protect him. Yet, note that when he hears Odysseus’ voice, he pricks up his ears, he lifts his muzzle. With effort, no doubt, with all the strength he has left in his poor, broken body. But he hears the voice of his master as he clings on to life. But why is he clinging on to life? The next passage further elaborates on Argos’ transformation upon hearing Odysseus’ voice: But when he knew he heard Odysseus’ voice nearby, he did his best To wag his tail, nose down, with flattened ears, Having no strength to move nearer his master. And the man looked away, Wiping a salt tear from his cheek; but he Hid this from Eumaios. Homer wants the listener to know that Argos did his best to wag his tail, to acknowledge that he recognised his master, to show a semblance of happiness and joy despite his current anguish. Homer doesn’t miss any of the details we associate with canine behaviour: Argos’ tail wagged, his nose was down, his ears were flattened. Yet, with so little strength, he could not move nearer to his master. He wanted to, we are led to believe. He wanted to run up and embrace Odysseus with the love and devotion only a dog knows. Odysseus is moved by what he sees; by the sufferings of his Argos. And he weeps. But, as he is disguised as a beggar, he questions his friend Eumaios about why the dog is in such a neglected state. Eumaios answers: “I marvel that they leave this hound to lie Here on the dung pile; He would have been a fine dog, from the look of him, Though I can’t say as to his power and speed When he was young...” And you replied, Eumaios: “A hunter owned him-but the man is dead In some far place. If this old hound could show The form he had when Lord Odysseus left him, He never shrank from any savage thing He’d brought to bay in the deep woods; on the scent No other dog kept up with him. Now misery Has him in leash. His owner died abroad, And here the women slaves will take no care of him.” With Odysseus’ absence came a string of suitors from nearby kingdoms to claim Ithaka as theirs, and to likewise claim Penelope, the wife of Odysseus. They feast continuously, gorge themselves on the fat of the land (of another), appear to be indifferent to the suffering of Penelope and the son of Odysseus – Telemachus. They are straight out and out thugs, parasites and ungrateful. It is they who have relegated Argos to the dung heap. It is they who have discarded him once he was of no use. It is because of these men that Argos is now bound by the leash of misery. Day after day, week after week. Dying a slow death when once he was the beloved of a King. But it continues: Eumaios crossed the court and went straight forward Into the megaron among the suitors; But death and darkness in that instant closed The eyes of Argos, who had seen his master, Odysseus, after twenty years. (Book XVII – Lines 375-422) Ah, what pathos, what beauty! I asked – why is Argos clinging on to life? And this probes me further, to reflect on that mystical connection between humans and dogs. To ask, do dogs know? Do they know of the mysteries of life, of the supernatural? Do they know when their master has died? Do they know when they themselves will die? Do they know that their master will return, so they must cling on until they – these faithful servants – lay their eyes upon them for one last time? You have been faithful with a few things, Christ uttered in one of his parables. Argos had been faithful in many things. He had clung to life, riddled with flies, starving. Tied up, not able to move, treated scornfully and with indifference where once he was treated with love and devotion. But he did not give up. This faithful servant knew Odysseus would come back. For upon seeing Odysseus, Argos’s eyes closed – those eyes that had just seen his master. Death and darkness enveloped him, he who had been surrounded by death and darkness in the world of the living. He clung onto hope, the hope that he would see his master. Job once asked: Where then is my hope— who can see any hope for me? He too had been relegated to life on a dung heap; scorned and ridiculed by men. He who once lived a kingly life. And when God revealed to Job the wonders of his creation, Job realised he was insignificant in the scheme of things. But he never gave up hope that God was with him. So too Argos; he never gave up hope. He clung with all his strength. He closed his eyes and although death and darkness enveloped him, he had seen his master as if risen from the dead. Homer wants us to care for Argos and his plight. He wants us to see a connection between Argos and Odysseus, a spiritual connection, a connection that reflects that mystical bond between humans and dogs that is eternal. Which will always be eternal. Dedicated to Angel, a beautiful Rhodesian Ridgeback cross who never got a chance at a second life.  Christ’s Holiness, Christ’s Humanity (continued) In this post-Christian world (so they say), I would like to share with you the paintings of a Russian Artist named Alexander Lepetuhin, who, upon being told by doctors he had only perhaps four years left to live, devoted his energies into his Faith. “Fine, I decided. Then all that time I will spend drawing Christ and his apostles.” Thus was born the Cycle of some 1000 Paintings of the Life of Christ and the Apostles. For further information, see: https://russian-faith.com/culture/renown-russian-artist-finds-out-he-dying-paints-1000-paitings-about-christ-n1555 5. The Road to Emmaus: Now behold, two of them were traveling that same day to a village called Emmaus, which was [e]seven miles from Jerusalem. And they talked together of all these things which had happened. So it was, while they conversed and reasoned, that Jesus Himself drew near and went with them. But their eyes were restrained, so that they did not know Him. And He said to them, “What kind of conversation is this that you have with one another as you [f]walk and are sad?” Then the one whose name was Cleopas answered and said to Him, “Are You the only stranger in Jerusalem, and have You not known the things which happened there in these days?” And He said to them, “What things?” (Luke 24:13-19) |

To find out more about me, go to 'About'. You can also follow me on Facebook: Archives

December 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed